The Rarest Pig

In the face of climate change, we commonly get caught up in the vast scale of melting Antarctica and flooding Florida. But it’s also good to step back and reflect on the everyday experience of wildlife biologists contending with saving just one form of life in one imperiled habitat. For such an example, see the Bawean Warty Pig (Sus blouchi). As its name implies, the warty pig is distinguished by the gigantic “warts” on its face. Why would a pig evolve such bulges on its ugly-enough head? For the same reason orangutans have side cheek pouches, and teens wear mohawks: To look larger and tougher than you really are. The blurred photo above suggests the photographer was anxious to get away before finding out.

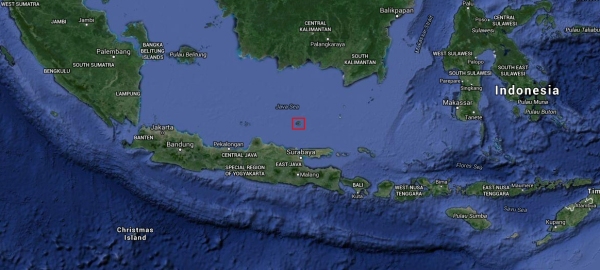

The warty pig lives in only one place on Earth: Bawean, one of Indonesia’s 18,307 islands. The human population of Bawean is so poor that women outnumber men 2:1 because the husbands have to work in Vietnam or some other richer place. Not surprisingly, much of the island has been deforested. And the forest is the only place where the warty pigs remain–less than 250 adults, by camera count.

So what’s a wildlife biologist to do? A PLoS ONE study by Mark Rademaker, Eva Rode-Margono and colleagues gives us some idea. They report the First Ecological Study of the rarest pigs on Earth. Note: The virtue of PLoS ONE is that you don’t have to prove to reviewers that your subject is “important.” You only have to show that you’ve done statistics that convince someone the results are “significant” (different from chance) as meant by mathematicians. Presumably the warty pigs are important enough to Mark and Eva that they spent two months there (November-December, 2014-2015, the same time as my season in Antarctica) on an island with no airstrip.

The most important thing they did was to record the animals. 690.31 camera-trap days, to be exact. By building up the counts over time, the researchers could show that the count “stabilized” by 500 days; that is, the researchers can claim mathematical confidence that their searching has counted most but not all of the few hundred warty pigs. For most of the pigs observed, the researchers also determined sex and age. How were sex and age determined? By the patterns of warts and of golden yellowish hair. Interestingly, the male to female ratio was 1:2, similar to that of Bawean humans. This point the researchers do not explain. Presumably the male pigs are not off working in Vietnam.

The researchers do spend a great deal of energy and mathematics on describing the warty pigs’ habitat preferences. They conclude, “We interpret the negative relationship between S. blouchi density and distance to nearest border as a direct link with increasing distance to the community forests at the edge of the forest.” In other words, pigs like to live in “community forests,” that is, forests managed by the local community with a say in land use decisions, and partial protection for wildlife. To its credit, Bawean island does maintain eleven protected nature reserves and three community forests.

The authors conclude with Conservation Recommendations: to declare the warty pigs Endangered, primarily on the basis of their small total number. Remember that such a small number of a vertebrate species can lead to inbreeding and genetic bottleneck. Fortunately the current population looks pretty healthy for now. So there’s hope for the rarest pig–thanks to their catching the eye of Jake-and-Neytiri-like starry-eyed biologists, with the financial support of the Indonesian Ministry of Research and Technology and the Office of Conservation of Natural Resources. As someone waiting on NSF right now, I sure can appreciate that one.

Comments are closed.

Hillary contributes this: